I ruined a perfectly fine evening listening to Shoenberg, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, Messiaen, Cage, Xenakis, Ligeti, Penderecki, and Part, but since I'd rather hear

Monteverdi or

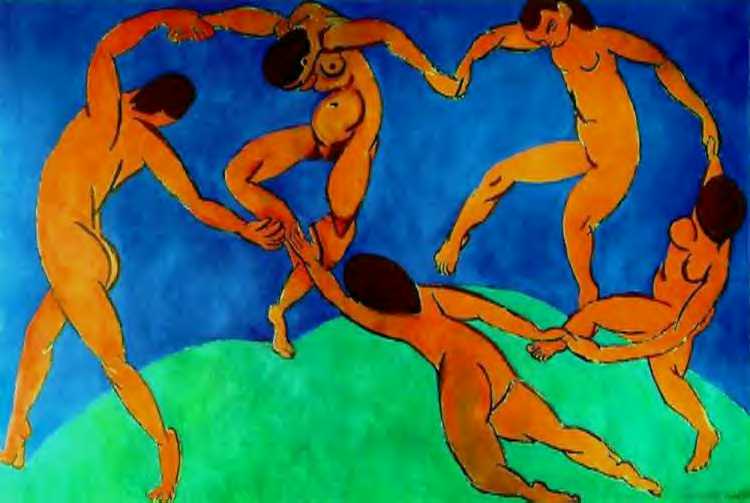

Schubert I'm some sort of small minded cretin? I guess open minded people are just the one's that agree with you. And what's all this talk about warhorses and museums? I like museums. Would it really be such a tragedy if the whole world happened to look like this

http://www.flickr.com/photos/4725704...44816627/show/ ?

I don't appreciate the implication that I'm somehow backward or mired in the past. I'm totally open to change and the new if I think it's an improvement. High speed internet, iphones, and solar power: sign me up. I'm convinced. But I haven't heard one thing on this board to make me believe that these space age bums are better than Beethoven. I haven't heard anything to make me suspect they are superior to Elgar, Puccini, Mahler, Debussy, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Rachmaninoff, Holst, Ravel, Prokofiev, Orff, Copland, Barber, Morricone, or Williams. I don't trust the way these new historians frame the narrative. When it comes to write the history of 20th century film it's going to be all Stan Brakhage and no Stanley Kubrick, and the Beatle's best tune wasn't Hey Jude, it's Revolution 9.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

But to get back to music:

But to get back to music: ). In such circumstances the intellectual/analytical part of me was pretty much turned off, but my appreciation and understanding of the music—some of it works and even composers that I had never heard before—was both deep and appreciative. Indeed, I think my understanding of some of the music I listened to in that time, without any thought at all as to its structure or an intellectual level analysis of its parts, was far more profound and taught me much more about what was going on in the music than some of the listening I’ve done when I’ve had in-depth intellectual knowledge of a piece or genre but been less attentive to it in other ways.

). In such circumstances the intellectual/analytical part of me was pretty much turned off, but my appreciation and understanding of the music—some of it works and even composers that I had never heard before—was both deep and appreciative. Indeed, I think my understanding of some of the music I listened to in that time, without any thought at all as to its structure or an intellectual level analysis of its parts, was far more profound and taught me much more about what was going on in the music than some of the listening I’ve done when I’ve had in-depth intellectual knowledge of a piece or genre but been less attentive to it in other ways.

To each his own. Yes, I think it's important to keep in mind that there may be a different sort of purpose or type of reward that comes from different kinds of art.

To each his own. Yes, I think it's important to keep in mind that there may be a different sort of purpose or type of reward that comes from different kinds of art.